TIBET CYCLING

LHASA

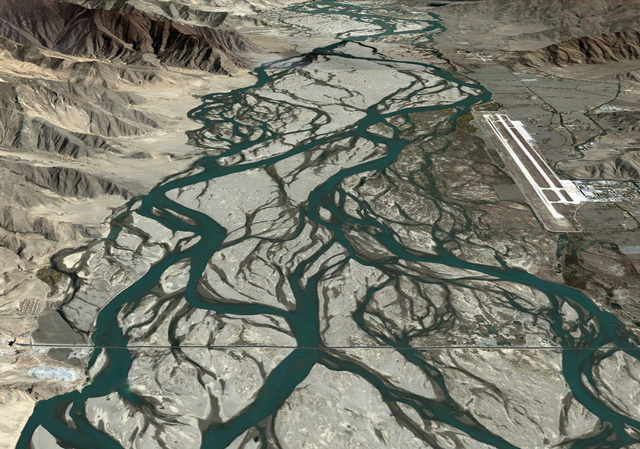

The arrival in Lhasa is by car. The surrounding mountains are steep and cragged and the topography is irregular. Thus, the airport had to be built some 100 km away from the city, where there is a narrow entry lane for the aircrafts. Chinese engineering built a straight asphalt snake from the airport to Lhasa swallowing the old Tibetan Lhasa with its head of concrete fortresses. The road is a foreign particle in this rigid and otherwise pristine environment. The large streams meander through the entire floodplains, quickly eroding the naked slopes of the nearby mountains. Yet, no farmer or engineer dared to tame the wild and unsettled streams. The farmers come when the water goes and they come again after the water once more has taken the sparse fertile land.

The paradox picture of the way to Lhasa is repeated when arriving in the city. Lhasa is a stone-built historical town surrounded by endless shopping malls, monumental administration buildings and concrete apartment blocks raised by the Chinese Province Administration. Lhasa appears as two different worlds within the same city limits. At the same time as the Tibetan part is squeezed in the centre, the outer boundaries of the city expand rapidly. The Chinese administration settles more and more Han people to extinct the remaining Tibetan culture and civilization. Only a minor part of the city is somewhat similar to what we expected Lhasa to look like.

When walking through the old part of Lhasa the time seems to be a different than elsewhere. People transport goods with Rickshaws, two-wheel tractors or with horses. The salespeople on the small street markets offer barley grist, butter, dry Yak cheese, teapots, brass saucepans, prayer-wheels and other Buddhist souvenirs for the tourists. The houses are built of stone, but the construction sites lack apart from rudimental cement-mixer any construction machinery. Bricks, mortar and timber are lifted by hand. The transport of material is often done by women and children. The buildings stand so close to each other that the narrow streets are almost blocked by people doing their activities in front of their shops and workshops. Tibetan houses are typically two-story buildings with a flat roof and a workshop in the ground floor. The Chinese authorities make all inhabitants to hoist a Chinese flag on the roof-top of their houses in solidarity with the People’s Republic. Ironically, only on the Tibetan houses. The Chinese architecture and city planning is a provocation itself to the old Lhasa. Chinese flags on the roof tops, surveillance cameras in front of the monasteries, KP monuments opposite of Tibetan sanctuaries, and huge boulevards for military parades are only a few examples of an unspeakable disfigurement in Lhasa. There is not a single square meter where the brute and obtruding Chinese influence is not visible. It gives the certainly unique appearance of the Tibetan city a tragic melancholia.

What remain are the tourist spots such as the Potala Palace, the Jokhang Temple, the Sera and the Drepung monasteries and the Barkhor Square. The latter has been the centre of numerous protests against the Chinese occupation during the last 50 years since the invasion in 1950. The latest protest in Lhasa took place in 2008 when thousands of monks and Tibetans demonstrated against the ongoing Chinese invasion. Several monks were injured and hundreds were arrested mainly through uniformed police forces patrolling in the old Tibetan Lhasa. By the time we stayed in Lhasa, we did not notice any indication of Chinese police or military, but one could tell that the people are afraid and suspicious towards most foreigners.

THE TIBETANS

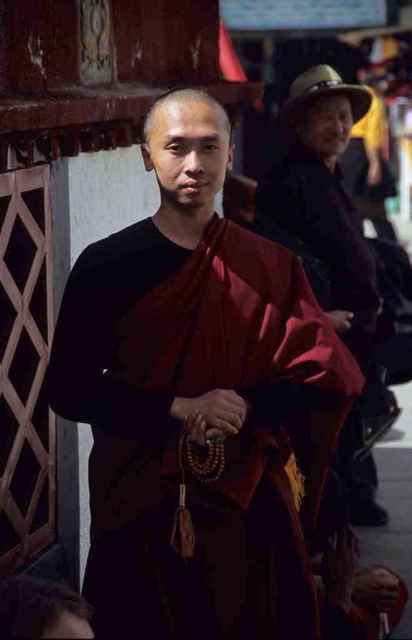

Our obligatory company in Tibet is Puchun, our tourist guide and Geysang, our driver. They are both Tibetan. Puchun lived in a monastery for 6 years where he gained some moderate English skills. He would support us with our preparations for the cycling trip and translate at least some of the Tibetan murmur. Apart from the practical difficulties, it turned out to be the challenge of the following days to gain an authentic impression of the Tibetan people and the life in the city. The people are daunted by the Chinese authorities and are carefully whatever they say or even think. It is only a few moments when we discover cordiality. An elderly woman on the street market gave us some cookies when we bought supplies, two school kids enjoyed a short trip on the bicycle rack over the Barkhor and a young monk exchanged a photograph of himself with one of ours. However, it was these short moments of elation that made us understand that the hospitality and courtesy exists, but is hidden behind thick walls of fear. In this respect it is rather frustrating to see how the truly beautiful nature of Tibetan people is trapped by the Chinese ignorance. The lack of interaction with the local people was the one and probably only negative experience while traveling this otherwise mind-blowing part of the world.

THE CYCLING

After having the car filled with Chinese dry food and vegetables from the Tibetan street market, we started the two weeks cycling tour. The route would lead us over some of the highest passes in the world including Pang La and Lalung La that cross the Himalayas in North-South direction. Usually, the scene was three cyclists ahead followed by an old Chinese 4x4 in a fair distance. Puchun (left picture) spontaneously bought in Lhasa a slightly over-engineered mountain bike to join the cycling group from time to time. The bicycle, however, ended up on the car’s roof top more often than on its wheels and finally was sold again in a small village on the way.

The proposed route by the Chinese follows the so-called FRIENDSHIP HIGHWAY. And a highway it is indeed: an asphalt giant, dividing the vast Tibetan Plateau into a Northern and a Southern hemisphere. It starts near Lhasa following Gyantse, Shigatse and Lhatse and finally turns south to cross the Himalayas towards Zhangmu and the Nepal border. The highway was officially built as connection between Nepal and China, but it is a well-known secret that the Chinese authorities want to enable rapid movement of police and military to Shigatse and to even more remote towns to oppress potential rebellions. Apart from a few cyclists and irregular columns of Chinese tourist busses carrying pilgrims to Mt. Kailash, not much traffic could argue for such a gigantic infrastructural project crossing the highest mountains in one of the most impassable regions worldwide.

The road follows mainly the river Yarlung Tsangpo which later in India becomes the Brahmaputra. On the last section to Nepal it traverses the main Himalayan range at almost 5200m above sea level. Some of the early stages are built as straight as drawn with a pencil whereas the ascents accumulate hundreds of small switchbacks. The more remote stages are still under construction and resemble an elongated mud pond rather than a road. At most times the route is abandoned. A few Chinese tourist caravans take over once in a while, but immediately after it is quiet and lonesome again. Nonetheless, after the first few stages we regularly left the main route to cycle on the smaller gravel roads offside the proposed route. We divided our way to Kathmandu into 17 stages including seven of the highest traverses in the central Himalayas. In the end, we will have cycled our bikes some 1100 kilometers far and more than 10.000 meters up and down the Himalayan Mountains.

then turns South climbing 1200 meters to the Kamba La Traverse. Passing the

Karo La traverse at 5050m, the route turns back in the highlands of the Tibetan

Plateau. We follow again the river Yarlung but this time in upstream direction.

This section of the route is among the most stunning, even though it continues in

rather moderate altitudes (~4200m). The road runs along the Yamdrok Tso Lake and

the bleak mountains, the turquoise water and crystal clear firmament create a scenario of infinite uniqueness and beauty. Not a single indication of life is visible alongside this untrodden environment. No grass, no trees on the bare slopes, no animals on the steep shores and, some say, not even fish in the lakes.

Instead, some Tibetan nomads slowly chase their decorated yaks along the deserted roads and young children play alongside. In fact it is the young Tibetans who have least constraints and regularly approach our camp to appraise the foreigners passing their homes. Even the routine preparation of butter tea with a brass kettle and PET bottle was stunning and carefully surveyed. It seemed that very few tourists come across this part of the country and the reactions were curious, but reluctant accordingly. On the other hand, it was releasing to see that the further we moved away from Lhasa, the more authentic became our impressions and the more faded the Chinese presence away.

Approaching Gyantse the picture alters. Small gravelly terraces along the untamed rivers allow the cultivation of barley, the main ingredient of tsampa, a Tibetan bread type. Flood events and a harsh climate, however, hinder the cultivation, due to soil erosion and barren soils. Along the route small settlements become more regular hosting Tibetan farmers that live from their Yaks and small-scale barley cultivation. When passing these nomad settlements it became obvious that some are only seasonally inhabited, as during the winter the people are moving around with their wild looking livestock (yaks). The yaks are the most important livestock that ensures the survival of the people in this misanthropic environment. They provide meat and give milk of which they make cheese and, of course, butter. The butter is used together with tea leaves and salt to cook tea, of which the local people consume up to 40 bowls a day. The houses are all built from self-made clay bricks. Clay is abundant on the slopes of the mountains and can be mined from the surface. Often dried yak manure is used to additionally insulate the houses from the outside to protect for night frosts.

Finally, the route reaches Shigatse, the second largest city in Tibet and home to a number of Buddhist sanctuaries and of course more Chinese settlements. One of the sites is the monastery Tashilhunpo that is renovated and re-opened for tourism of all kind. Shigatse is at the same time the last major town before entering the less and less populated foothills of the main Himalayan range. Travelers can stock their supplies and take the last recreation before facing the awaiting ascents to the highest traverses on the tour.

The last flat sections lead through a picturesque expanded river valley ending in Lhatse, the very last stop before the upcoming climbing. Lhatse is a little village at the foot of the first North-South traverse. The village is quite lively as it is the supply base for the construction works of the pass starting a few hundred meters behind the village. The road which is now the already mentioned mud hole climbs around 1500 meters to the peak of the tour, the Gyatso La traverse. We need to camp a few km before the peak meaning that we cycle some 200 m altitude higher than our camp to adapt to the height. As if this double taxation was not punishment enough, we encounter snowfall during the night and the first few kilometers up to the peak are not muddy anymore, but even worse, namely slushy.

Latest from this point the road outstrips all somewhat-flat-terrain. Traverses over 5000m a.s.l. succeed in shortening interspaces and the endless ranges of ice-capped peaks alongside the route come closer and closer. Among the toughest ascents is the Pang La traverse with no less than 47 switchbacks upwards and 43 downwards on the subsequent descent. At this point Geysang, the driver, lost patience with curving the car around the turns and took the straight way downhill. Trying a few more turns, eventually, we followed his example and experienced some of the most exciting downhill sections one could wish for.

We chose the route passing the Chomolungma Base Camp. It is located a little South of the main route and poses the starting point of countless expeditions during the spring season. The gravel road resembles a wash board, being galled through thousands of trucks carrying mountaineers, climbing gear and photographers to and from the base camp. Cycling without a suspended bicycle is a challenge on its own, irrespective from the steady and increasing slope. After Shigatse, the Rongbuk monastery at the base of the Chomolungma is the second real destination we were desperate to reach. The monastery is located 7 km downstream the Base Camp in the moraine formed trough valley that has been left behind by the retreating glacier. Here we pitch our tent in front of the shrine and with a breathtaking view on the Chomolungma peak. During this season it is not many travelers granted to see the mountain of all mountains bleak and uncovered. We were among them.

We continue the route in North-Western direction back to the river valley for the last few dozens of kilometers before finally turning south to cross the main Himalayan range. The route is now literally a route far from having similarity with a regular road. Sometimes the only navigation is uphill. Finally reaching the plateau, we come across nomads with their yaks who are the only creatures who still feel home in this misanthropic environment. More than once we have to shoulder our bikes and wade through some of the cold meltwater streams that have the same intention as we have ourselves: finding the shortest way down to the Yarlung river valley.

The last challenge on the route through Tibet is the double-peak of the Lalung La. Both traverses are above 5100 m a.s.l. together they constitute the final crossing of the Himalayan range. It is a bare and deserted mountainous environment we are passing, but it is one of the most stunning ones at the same time. Similar to one of the early stages the total non-existence of any kind of life gives these mountains an aspect of awe and uniqueness. The traverses appear peddling in the face of the beauty and pride of the surrounding summits. Once reached the top, we checked the traverses number seven and eight off our list, of which seven are above 5000 meter: a satisfying result for all of us.

Name of Traverse |

Peak elevation |

Diff in altitude |

Kamba La |

4789m |

1200m |

Karo La |

5050m |

780m |

Gyatso La |

5220m |

1250m |

Pang La |

5190m |

940m |

Rongbuk |

5145m |

1050m |

West Traverse |

5090m |

520m |

Lalung La II |

5120m |

900m |

Lalung La II |

5160m |

260m |

From here the route falls 4500 meters into the Terai in Nepal. Some sections pass steepest canyons and the little road that was hammered into the vertical walls seem as fragile as a string against the massive rock. For two hundred kilometers our bikes roll almost without pedaling. Down, down, down. So far down, that even after climbing traverses for two weeks, it becomes a bit boring. Finally we reach Zhangmu, the last city on the Tibetan side and the end of our guided tour with Puchun and Geysang.